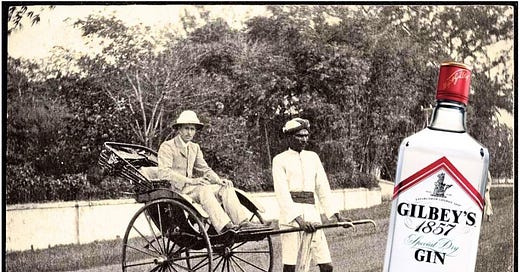

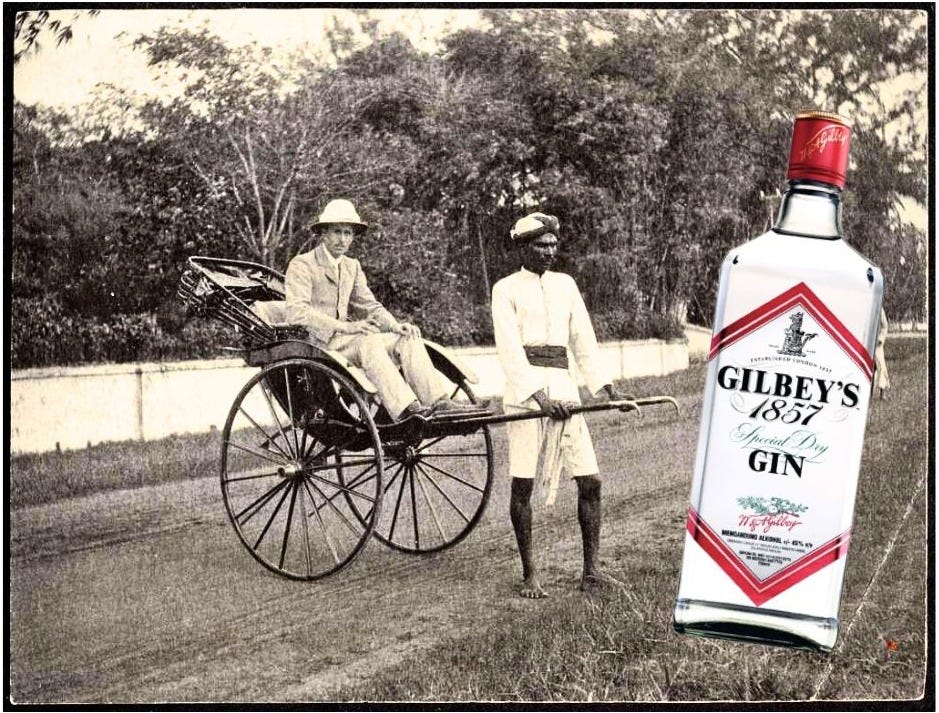

If gin were a person, it would be a ruddy-faced man with grand muttonchop whiskers, wearing jodhpurs and a pith helmet, carrying a riding crop, and standing amid a riot of tropical growth with an aloof, haughty air. Because gin is colonialism personified.

Historically, gin was both engine and lubricant for two great colonizing empires: Holland and Great Britain. In both, it served at least three purposes: as a trade good used to acquire spices, local services, and slaves; as a component of a medical remedy—mixed with bitter quinine to combat malaria; and as a liquid antidepressant for plenipotentiaries, factors, and commercial agents stationed in distant tropical ports, where tumblers of gin dulled their longing for home.

Yet in the last couple of decades, gin has emerged as a different character and reinvented itself globally. This quiet revolution has been widespread and significant. Gin is now less a colonizing caricature and more a local bon vivant—an enthusiastic ambassador for regional flavors

.This transformation might not be immediately apparent when walking down the gin aisle of your local liquor store. Just as American whiskey is still marketed as a rugged frontier spirit — square bottles, raised type, antiquated fonts, stern-looking men — classic gin bottles often echo the marketing of a century ago. Since the 1930s and ’40s, gin has leaned into its association with exotic, far-flung lands. Barclay’s Gin featured a mahout and elephant in its advertising; Calvert Gin ran ads with a mustachioed ”Sir Gibson Drysdale” in “full desert kit.”

Of course, marketing rarely emphasized two of gin’s three historical roles. Its use as a malaria treatment or “trade gin” in African and Asian commerce was considered too exotic—and maybe too uncomfortable—to highlight.

Instead, 20th-century branding played up the romanticized aspects of colonialism: Europeans living unconventional lives in uncomfortable climes. It was the era of Joseph Conrad, Somerset Maugham, and Graham Greene—and of films like The Drum (1938) and Diamond City (1949). The fantasy was that life abroad was adventurous and glamorous; the reality of exploitation was conveniently set aside.

Today, that colonial romance still lingers on gin bottles. Plymouth Gin’s label shows a sailing ship bound for unknown adventures. Tanqueray’s emerald-green, cocktail shaker–shaped bottle dates from the 1940s and would look at home on a rattan table in Pondicherry. Bombay Sapphire takes its name from the famed gem “Star of Bombay,” itself linked to colonial history in Sri Lanka. And Cadenhead’s Old Raj Gin—well, just look at it:

Even Hendrick’s Gin, launched in 1999, evokes a Victorian cabinet of curiosities—oddities gathered by a globe-trotting Edwardian explorer. The apothecary-style bottle, with its 18th-century scrollwork label, looks as if it were just unpacked from a straw-lined crate.

But the story of today’s gin is quite different. Gin has, in effect, reclaimed an antiquated narrative and made it its own.

Gin was once synonymous with Great Britain and Holland (though vast quantities were produced in the United States in the 20th century). Today, it’s distilled in virtually every corner of the world. The World Atlas of Gin (2019) lists 54 countries producing gin — and many more have likely joined the ranks since.

Where old-world gin was a symbol of empire — its juniper, orange peel, and other exotica arriving aboard fleets of merchant ships — the new gin era is rooted in local identity and authenticity. Distillers worldwide are embracing indigenous botanicals and terroir, crafting spirits that reflect their unique environments rather than distant colonial myths.

This evolution is fueled by consumers’ growing demand for provenance, sustainability, and distinct flavor profiles that tell a story of place.

Craft gin producers are working with locally sourced ingredients—from native herbs and spices to regionally grown juniper—creating expressions that celebrate biodiversity and cultural heritage.

A few examples:

Peru. London to Lima Gin uses a pisco base and botanicals inspired by the diet of the Andean bear—berries, fruits, honey, and palm hearts.

Kenya. Procera Gin is made in Kenya, a British protectorate from 1895 to 1963. It’s named after a juniper variety that grows only in Kenya and Ethiopia and is made with Swahili limes and pixie tangerines, both locally sourced.

India. Uttar Pradesh, once a focal point of British colonial rule in India and a base for the British East India Company, is the birthplace of Jaisalmer Indian Craft Gin. Seven of its 11 botanicals highlight regional flavors, including Darjeeling green tea, cubeb berries from southern India, and coriander and vetiver from the north.

Gin has transformed from a relic of empire into a spirit of place—one that resonates with contemporary values and tastes while honoring the diverse landscapes and cultures from which it springs. It makes exploring the liquor aisle far more adventurous. No pith helmet required.

This reads great, but vanishingly few of the novel gins I’ve actually tasted (admittedly, a very small minority of what is now available) have been compelling. Too weird, or simply forgettable. There was one, though: an Elg gin from Denmark with carrots amongst the botanicals. Mostly a classical dry gin, but the carrots were definitely there, and it was not a bad thing.