How Floating Bars Defied Prohibition

The forgotten story of one of America‘s more ambitious attempts to circumvent the 18th Amendment

In 1924 a large and mysterious ship was spotted about 15 miles off the coast of New York’s Long Island, idling and going nowhere. “It was a nameless ship,” reported a newspaper, “whose huge bulk by day and maze of glimmering lights by night had mystified the residents of Long Island.”

An intrepid Herald-Tribune reporter decided to head out to investigate. The trip didn’t go smoothly. The engine on the runabout ferrying him and others to the mystery ship conked out, and they drifted for hours before eventually flagging down another boat headed to the same ship.

The unnamed ship turned out to be a glamorous offshore bar. To get aboard the reporter paid a $5 cover charge (about $90 today), with another $5 for a stateroom. Once settled, he was ushered into a festive room with “a jazz orchestra, staff of busy bartenders and a party of sixty revelers who danced the night away.” They were young and old, men and women, but all quite wealthy with “polished manners and a democratic demeanor.” The crew was well dressed and spoke with cockney accents; from them one could order a scotch for $1 or a mint julep for $2.50. Bottles of wine could be had for $20, and champagne was “in abundance at fat-purse prices.”

Speakeasies and rum-runners play a central role in the modern mythology of the Prohibition era. It’s all smugglers at sea and bartenders in basements. Overlooked, however, are the offshore drinking destinations, variously referred to as “floating bars,” “sailing thirst parlors,” “sea-going booze palaces” and “maritime saloons.”

These barrooms at sea were legal, although they also sort of weren’t. They were initially anchored three miles offshore, which became 12 miles after international waters were pushed back in 1924. Accounts suggested that these floating bars surfaced because the captains who parked their smuggling ships along “rum row” — that is, the invisible line that demarcated international waters — were bored sitting around waiting for smaller smuggling craft to arrive to load their crates. They saw the opportunity to have some fun while making bank

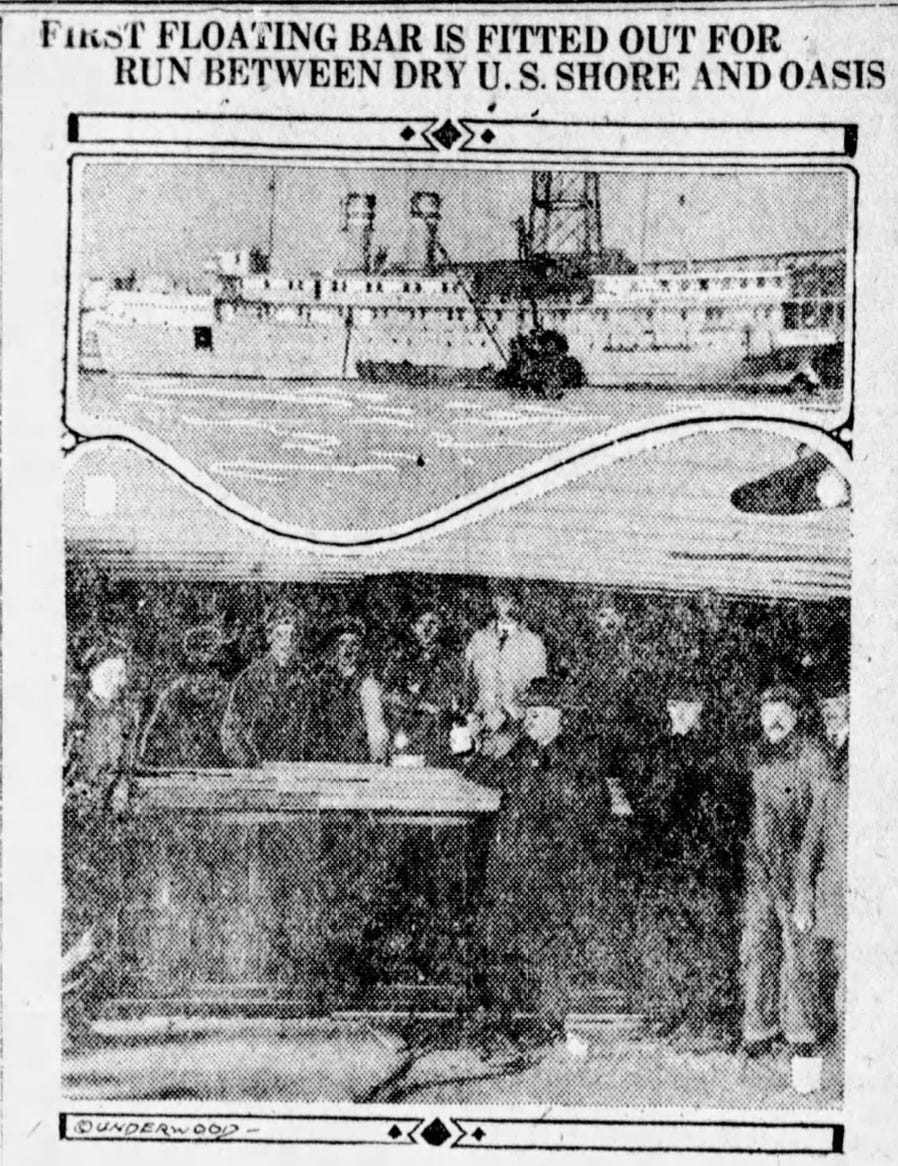

The first announced booze palace was the “City of Miami,” a floating bar that planned to make three trips weekly between Miami and Havana. The scheme was announced in February 1920 by “New York and Milwaukee capitalists” less than a month after Prohibition went into effect. The ship would be equipped with an “elaborate bar on the afterdeck, complete in every detail,” and passengers would be afforded “all the conveniences outlawed by the eighteenth amendment.” Regrettably, when the captain arrived at the shipyard to take possession, he found the capitalists failed to pay the $400,000 for the retrofitting and the ship had been seized by creditors. There’s no indication that it ever sailed the sodden seas.

Indeed, there were more plans for these offshore oases than deliveries, making these the drinker’s equivalent of vaporware. These may have been an excellent idea., but many foundered on finances and the vagaries of prohibition law. (Authorities said that while such ships might be legal in international waters, those shuttling into international waters could be arrested for “going foreign.”)

Still, excited rumors arose in California of a floating bar 12 miles off Los Angeles, complete with a water taxi service. “Thirsty Rejoice over Rumor of a Sea Bar,” read one headline. (Its actual existence was never confirmed in print.)

In Texas, a debate arose over the wisdom of selling off a small fleet of unused wooden boats to liquor interests who would convert them to offshore bars. Texas was evidently less enthusiastic than California about the prospect.“Should the wooden ships be converted into floating bar rooms outside the jurisdiction of the United States authorities,” one killjoy wrote, “they would soon degenerate, in the absence of police regulation, into such places of debauchery and vileness as to disgrace the American nation.” Alas, no evidence that such debauchery ever came to pass.

New York was where the money was, and it was here one of the more ambitious endeavors was planned. A fleet of as many as three floating liquor palaces was announced by entrepreneur James V. Martin, who said the first would be constructed in Europe for a whopping $10 million and it would be as large as the The Leviathan, a noted liner that held 1,800 passengers. Did it happen? There’s no proof that it did.

Yet some offshore bars did exist, if less grand than the one visible from Long Island. Off the tip of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, a pair of enterprising fishermen rigged out a fishing boat with a bar complete with brass rail overseen by an “accomplished fisherman-bartender.” News accounts reported that they ”gave up their lobster pots to lure fish from Park Avenue and Greenwich Village,” and were so popular that guests had to reserve a motor launch shuttle a day or two in advance. (”Some have resorted to rowboats.”)

Many more maritime saloons may have quietly existed — avoiding the glare of publicity would have been part of the business model. Word of mouth, which would have been the main driver of business, doesn’t often survive to the next generation. But in our current era of celebrating “disruptors,” let us give credit to those who considered the complications and legal jeopardy of bringing illicit booze ashore, leaned back in their club chairs, exhaled a cloud of smoke, and thought, “Why bring the booze to people, if you could bring the people to the booze?”

We salute you, anonymous tenders of the undocumented offshore cocktail convoy.